It’s been a very cold winter in these parts, and I’m back to playing around with Family Search’s full text search. I needed a break from Smiths after sorting out the two Daniels, you see!

With this last round of digging, I learned that my 3rd great-grandfather, Daniel Smith (1816-1868) was relatively well off. In 1860, for example, Daniel listed a net worth of $2,400 in real estate and $1,900. That included no slaves, as far as I can tell. His 1868 estate inventory makes it clear that he was a livestock farmer, with 50 head of cattle, 50 hogs, and 40 sheep. It also included some accoutrements of middle-class life, such as a clock, and a table with 10 chairs. In addition, it appears that both Daniel and his wife, Sarah Hart Smith, were literate, which put them in the minority in the South at that time.

Daniel’s brothers were similarly well-situated. And, I have yet to find them on any slave schedule or recorded in any slave transactions either. The family was strictly Methodist, and, unlike many others, seems to have taken seriously the injunction not to hold slaves. This was a good decision for obvious reasons, but also meant that they were not as impoverished by the Civil War as they might have been otherwise.

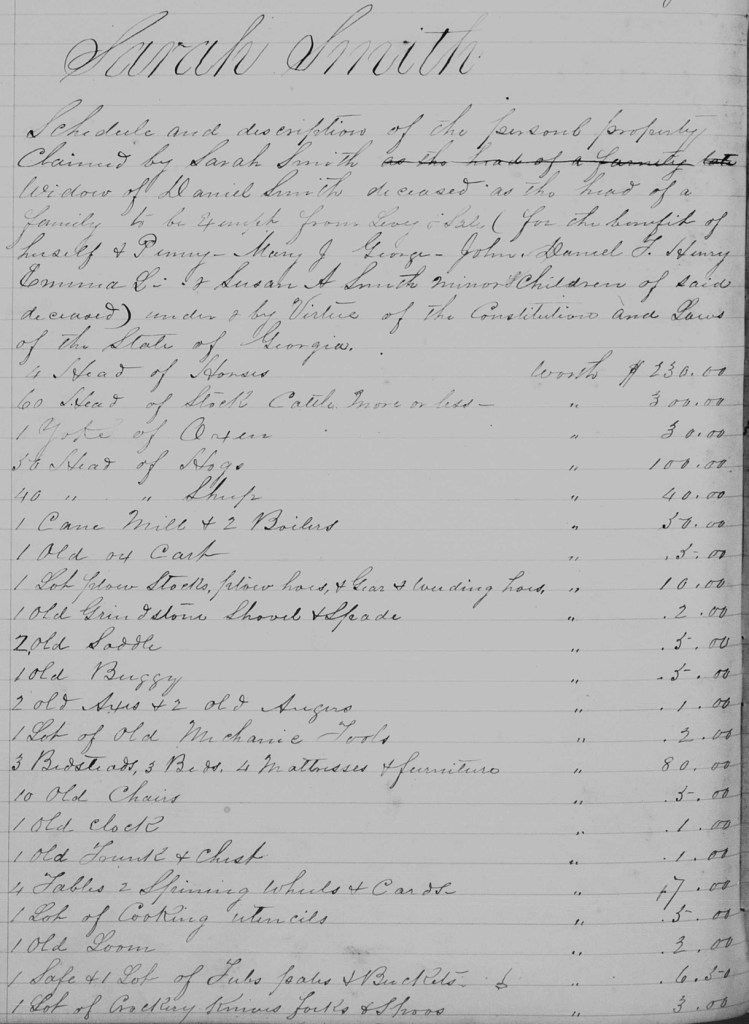

Daniel Smith died at age 52 in 1868 of “congestion of the brain,” which could have been meningitis, encephalitis, or a stroke. His wife, Sarah (1824-aft 1885), was left with 10 children, all but one under the age of 21. Being a smart cookie, she immediately went to court to have her property declared a “homestead,” which exempted it from being sold to pay debts. She owned three lots in or near the town of Drayton, in Dooly County, Georgia which totaled approximately 600 acres.

Sarah continued to manage the livestock farm with her children for decades. In 1870, she is listed as head of household, with a real estate value of $1500, and a personal estate value of $1,125. By 1880, just one of her parcels of land, presumably the one on which she lived, was valued at a substantial $1,800 (it is possible that this is an error on the schedule and is actually the total value of all her land).

By 1885, all of Sarah’s children had reached the age of 21, and she was getting on herself, so she petitioned the court to allow her to sell the other two 200-acre parcels of land comprising Daniel’s estate to divide among his heirs. The petition also states that she was debt-free, so evidently a successful farmer herself.

At this point, Sarah had eight surviving children. Three grandchildren by a daughter that had passed away were also declared heirs. Of course, 400 acres of land divided between at least nine heirs does not amount to very much for each legatee! While the most of the Smith offspring were blessed with good, long lives for the times, lots of kids, and good educations (all three inherited from their apparently very capable mother) their financial fortunes steeply declined.

My great-great grandfather, George Washington Smith (1853-1932), was the fifth of Daniel and Sarah’s kids. He married Lucy Ann Goodman (1857-1930) in 1874 in Dooly County. Lucy was from another literate, farming family. George inherited a small amount of land (or the proceeds thereof) in 1885, and may have inherited a bit more when his mother passed away. However, I have not found any evidence that he ever purchased land of his own until a series of odd transactions in Dooly County in the 1890s.

On 26 July 1898, George purchased a lot in the center of the town of Unadilla, Georgia, from R.L. Wilson. The same day, he purchased an adjacent lot from Wilson’s wife, Sallie. He paid $600 for the first lot, and $1000 for the second.

One year later, on 9 August 1899, George sold the combined lots to the Equitable Building and Loan Company for $1,000, total, a considerable loss from the original purchase price. My guess is that he was unable to make the payments on the loan, so was forced to sell.

Shortly afterward, Sallie Wilson took George to court, claiming that she was still owed $786 from the original purchase. She could not find the original promissory note, but the court accepted a copy and ruled in her favor. A lien was placed against George’s property “both real and personal” to pay the debt. As I have found no evidence that George actually owned any other property, this judgement must have wiped him out. He had placed a bet, and lost, big time.

Just a few months later, George and Lucy Ann are found in Hamilton County, Florida. It is possible that they left Georgia in order to avoid repaying the note to Sallie Wilson. In 1900, they are found farming on rented land, meaning that they were sharecroppers. George continued to farm a share and later, to work as a store clerk–because he still had his education, after all.

Lucy Ann died without a will in 1930, and very interestingly, left behind a bank account at the Commercial Bank of Jasper, in her name alone, with $202 in it. This was a fair amount of money at the time, and certainly could have been useful to a sharecropping family. I just wonder where she got this money? Did she inherit a little bit at some point? Did she squirrel away “egg money” or dressmaking proceeds? Did the rest of the family even know about it? One thing is for sure, she made certain George couldn’t get his hands on it!

And George never did. After Lucy’s death, George petitioned the court, along with his kids, to divide Lucy’s estate. (This is the first time in my research that I have run across a husband petitioning to divide a wife’s estate rather than other way around.) The court delayed judgement for unspecified reasons, and it wasn’t until five days after George had passed away himself, in 1932, that the bank account was released to the custody of Lucy’s son, Daniel Thomas Smith to be divided among his siblings.

I do wonder a bit about that timing: did the court decide it was not a great plan to allow George to administer the money? He was almost 80 at the time, perhaps he was not considered to be competent. Or perhaps he had never been competent with money, and that is why Lucy decided to quietly build her own security. In any case, here’s to my sharecropping great-great grandmother and her rare, small act of independence.