Slaveholding families held much of their wealth in human capital. And so, they often argued about slaves. When they did, they left court records which provide a lot of information about both themselves and the enslaved people that they were arguing about. David Neal’s family is a case in point.

In his will, dated 4 June 1775 in Amelia County, Virginia, David Neal left his son Roger two enslaved men, Adam and Ned. He left a woman, Bett, and her children to his daughter, Mary Morgan, He also left his two grandchildren by his daughter Eleanor Neal, William McGuffey Rives and Joanna Rives Turner, “one Negro Woman Named Phillis and all her Children to be Equally Divided between them” after his wife, Joanna’s, decease.

David Neal made the point that he did “hereby Revoke and Make Void all former Wills by one made either by Word of Mouth or in Writing.” This is because he was apparently was in the habit of changing his mind a lot. More on that later. But one of these previous bequests, dated 23 May 1768, gave to “my two grandchildren William Rives and Joannah Rives, son and daughter to Thomas Rives, four negroes and their increase, named Phillis, Dusillah, Doll and Marriah after me and my wife’s decease, to be equally divided between them.”

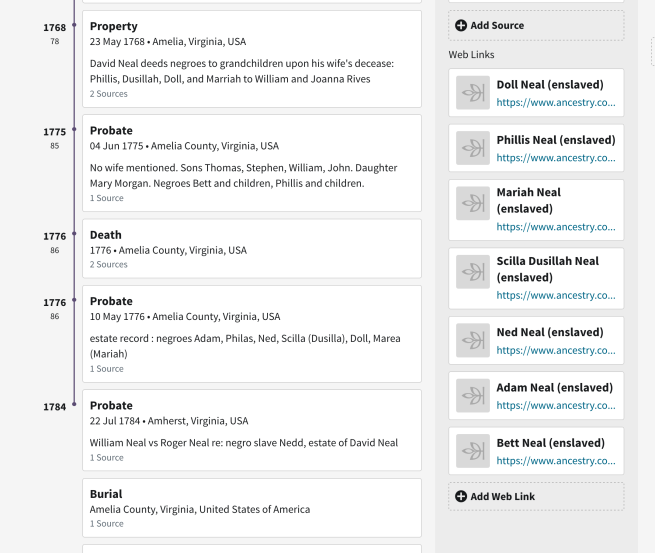

David’s estate inventory, dated 10 May 1776, names one “old Negro man,” Adam, one “Wench” Philas, a Negro man, Ned, one “young wench” Scilla (Dusillah), and two girls, Doll and Marea (Mariah).

Joanna Neal must have died by 1786, because a Mecklenburg County, Virginia court decision dated 19 Dec 1786 divides up Phillis and her children, naming them in the process.

Phillis and her daughter “Murriah” (Mariah, or the “Marea” named on the estate inventory) went to William McGuffey Rives.

Joanna Rives Turner received “Siller” (Scilla, or Dusillah) and her child Milley and Doll and her two children Adam and George.

From these documents we can piece together the following family:

Phillis was likely partnered with Adam, because her daughter, Doll, later named a son, Adam, presumably after his grandfather. Also, Ned is referred to as both a “man” on the inventory, but a “boy” in a later court case. So, it does not seem like he would be old enough to father several children by the time of the will. He is more likely Phillis’ oldest son. Bett, who was old enough to have children by 1775, may be an older daughter of Phillis and Adam. But there is nothing that actually indicates these relationships, so I am not linking Ned or Bett to Phillis and Adam at the moment.

Phillis’ named children were Mariah, Dusillah, and Doll. We know that all three were born before 1776, because they are named on the estate inventory. In fact, let’s say before 1775, because they are mentioned in David Neal’s will of that year, if not specifically named.

Mariah is most likely the youngest, because she is “packaged” with her mother in the 1786 settlement.

We know that Dusillah has a daughter, Milley, by 1786. So, even given the shockingly young ages at which enslaved females bore children, we can reasonably assume she was at least 13 in 1786, therefore, born before 1773.

We know that Doll has two children by 1786, so I will assume she is at least 15, and therefore, born before 1771. Her two sons, George and Adam, can be listed as born before 1786.

Working backward, if Phillis already had at least one child by 1770, she can be assumed to be born before 1757 (or more likely several years before that, if Ned and Bett are also her children). The elder Adam was also born no later than 1757, but I am going to assume that he would have to be at least 40 to be considered “old” in 1775. Therefore, I am going to make his his birthdate before 1735.

And so I ended up with the following family. This has been uploaded to Ancestry as a “floating” tree linked to the various enslavers via web links and the documents listed. I always use “AA” to indicate “African-American” because “enslaved” does not make sense for individuals who can be traced after emancipation. More about this system here. (I should note that I did not personally come up with the idea of adding enslaved people as web links. I got it from this video by Crista Cowan.)

Note that I only use the surname Neal because it is too confusing to have dozens of people with “Unknown” as a surname in my database. I know that they may have used no surname, a different surname or changed surnames over time. Also, Ned and Bett have also been added to my tree, but unlinked to Phillis and Adam as I don’t know for certain that they are related.

All of these people were presumably in Amelia County, Virginia up until 1786. However, it’s worth noting that William McGuffey Rives lived in Mecklenburg County, Virginia by the time he received his bequest, therefore, Phillis and Mariah would have moved there, and onward to Warren County, North Carolina by 1790. Fortunately, Joanna Rives Turner moved to the same district of Warren County with her husband Terisha Turner II, so at least Phillis would have been near her other children. Adam (if he lived that long) and Ned, however, would presumably have stayed behind in Amelia County with Roger Neal, who inherited them in his father’s will.

More about Ned: he was the subject of a court case in 1784. David’s son, William Neal, sued his brother, Roger Neal, in a failed attempt to gain possession of Ned. William in his oral argument, claimed that, his father “desirous of advancing your said Orator’s fortune, did Verbally give unto your said Orator one Negro boy slave known by the name of Nedd.”

William testified that because he was concerned to formalize the arrangement, he did give his father “the sum of Three Pounds for the purchase of said Slave.”

But then Roger, as executor of his father’s estate, “hath taken into his own service the aforesaid Slave who is and ought to be the property of your Orator…refusing to deliver him to your Orator although after requested thereto in a friendly manner alleging that your orator hath no manner or right or Title to the said Slave, the contrary whereof he knows to be true. All of which actings & doings of the said Roger are contrary to Equity & good Conscience and tend to the injury & oppression of your Orator.”

(I just love how this young white man is claiming that he is being “oppressed” because he can’t have the slave that he believes he is entitled to, but anyway…)

William’s brother Roger, however, had a different version of the story. According to him,

“… his father David came home one Evening much in Liquor and his son the Complainant that he would give him a negro a conduct which under the like circumstances this old Gentleman was much addicted to & repeated as often as he happened to have drank too much

The Complainant replied that such a Gift would not do, and that must give his Father something for the negro to give it the appearance of a Bargain between them, whereupon his Father told the Complainant to give him a piece of Bread.

To which the Complainant replied that that he would do, but that he would give him a forty shilling Bill (as this Defendant to the best of his memory, thinks) which did accordingly, and his father being still much intoxicated fell asleep.

In the morning, the Defendant’s Mother, asked her Husband the said David Neal if he remembered what he had done the night before, to which the said David answering in the negative, she told him that he had sold the slave Ned, in the Complainant’s bill mentioned to his Son William and that in order to confirm such sale the said William had given him a forty shilling Bill.

Whereupon the said David searching his pockets & finding such a Bill therein, called the Complainant and told him he had no notion of any such bargain and bade him to take back his money which he then delivered to him of the Complainant and accordingly took the same back…

Roger was most indignant and continued…

This Defendant can not but observe that from the Complainant’s own _____ in his Bill the Transaction on his part appears to have been fraudulently intended in order to evade the Operation of an act of assembly, this Defendant solemnly averring that his Father as far as might be collected from the nature of the whole transaction to which this Defendant was an Eye-witness had no Intention whatsoever of selling the said Slave to the Complainant.

Without that, that there us any other or Thing & this Defendant denied all unlawful Combination & prays to be dismissed with his Costs in this behalf most wrongfully sustained.

The case apparently dragged on until at least 1791. I have been unable to figure out exactly what judgement was made, but as Roger was actually bequeathed Ned in David Neal’s final will, I am going to assume he won.

This story is a good illustration of why it pays to research both the slaveholders and the enslaved: I now know much more about my hard-drinking Irish 7th great-grandfather and his family than I would be able to tell from census records, that’s for sure!

Finally, to the point of this whole exercise. This is what Ned’s record looks like on Ancestry now. The documents and transcriptions are now available to anyone who might be looking for him.

And anyone who is researching David Neal will also be able to see the names of the people he enslaved along with relevant documentation.

I hope that information is helpful to both Neal researchers and to anyone else who may be wondering how to include enslaved people in their family tree.

Please keep doing what you’re doing. Teach me how to do it, too. I’m finding estate records in the South with hundreds of named slaves. Adding these to Ancestry family pages in an easily accessible way is daunting.

Ancestry does not make it easy. Your comment about “whitewashing” is spot-on. The platform makes it difficult to find these records and then the researcher has to jump through hoops in order to get them posted in a coherent way. (I still cannot get most Slave Schedules to appear in Facts as a separate event.) All the while getting Confederate battle flags and Southern apologetics quotes as “hints” for southern ancestors. Pointing this out to Ancestry and complaining has not been productive.

Thank you! Jana Trent

>

LikeLike

I am glad you found it be to helpful! It is overwhelming, once you start really digging into the history, how many slaveholders you find.

Here is a link to my previous post on adding enslaved people to the family tree, in case you want more information. https://longwaytotennessee.com/2019/01/30/finally-adding-enslaved-people-to-my-family-tree/

LikeLike

I’m excited to have found your blog. I’m just starting to dip my toe into researching the many slaveholders in my tree. I’ve been duck my head and looking at other family branches for decades, and it’s time to dig into this overwhelming topic. I’ve looked at the Beyond Kin Project method but haven’t actually taken the plunge yet. I look forward to reading your other posts!

LikeLike

Thanks! Get ready, once you start uncovering those records they just keep coming…

LikeLiked by 1 person